The physical impediments to a woman in a burqa are obvious. She is confined, the air hot and suffocating under layers of fabric. The cap fits tightly around her head, often causing massive headaches. She has no peripheral vision—dangerous enough when crossing streets and walking through the bazaar, but there are other, insidious consequences. She can see only what is in front of her. If she hears a voice from the side and turns to identify the speaker, her intentions are revealed. She cannot look at anything or anyone freely. She never knows who may be watching.

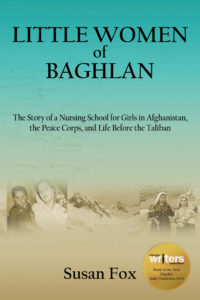

—Excerpt from Little Women of Baghlan, Susan Fox

The description is from 1969, Afghanistan, as experienced by Jo, an American Peace Corps Volunteer, working in Baghlan. She teaches nursing to a group of young Afghan girls, including Anorgul, the girl in the photo, posing with her younger brother.

The late 60s are a time of promise in Afghanistan; the country is at peace, making progress toward becoming a modern nation. It is a time of transition, so although there are still women who follow the old tradition, living behind burkas, there are others, young girls like Anorgul. Girls who are going to school, anticipating a better life.

And then the Russians invade Afghanistan.

In 1979, not long after Jo returned home, Soviet tanks rumble into Afghanistan, igniting a ten-year war. Afghan guerilla fighters—the mujahideen– force Russia to withdraw in 1989, but not before 15,000 Soviet soldiers are dead, along with roughly two million Afghan civilians. Homes, farms, and entire villages are destroyed, leaving millions of Afghan families homeless, internal refugees in their own country.

Since then, Afghanistan’s timeline reads like a systematic litany of tragedy and failure.

With Russia out of the picture, and no semblance of a central government, Afghanistan falls into disarray. Chaos becomes Civil War, causing more destruction, more Afghan deaths.

The Taliban emerge out of Kandahar in 1996, and take control of the country with one, powerful promise—they vow to restore ‘law and order.’ Tired of fighting, the Afghans eagerly embrace this new sect, but they pay a high price. The Taliban notion of ‘Law and order’ is nothing more than an excuse for the most severe interpretation of Islamic law, in particular laws that strip women of their rights.

Then on September 11, 2001, militants associated with the Islamic extremist group al Qaeda hijack four planes and fly two of them into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing some 2,750 people. The United States retaliates, and one month later, on October 7, 2001, U.S. and British warplanes pound Taliban targets. Dubbed Operation Enduring Freedom, the campaign is designed to remove the Taliban from Afghanistan and dismantle al-Qaeda.

President George H.W. Bush promises financial assistance for the operation, but from the start, development efforts in Afghanistan are poorly funded. To make matters worse, in March 2003, the United States invades Iraq. Almost immediately, resources, military support, personnel, and attention swivel from Afghanistan to the Iraq War. (Readers may remember the Tom Hanks movie “Charlie Wilson’s War.) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0472062/

Now, with the spotlight directed the other way, the Taliban mount a slow and methodical resurgence. They take advantage of anti-American sentiment among Afghans, feelings that are amplified by the sluggish pace of reconstruction, allegations of prisoner abuse at U.S. detention facilities, widespread corruption in the Afghan government, and civilian casualties caused by U.S. and NATO bombings.

On April 14, 2021, President Joe Biden announces full troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, a process that begins on May 1, 2021.

Afghanistan has been called the “Graveyard of Empires,” a phrase that has survived from antiquity. When the Afghans drove the Soviet Union from its borders in 1989, that fact should have been a red alert, a lesson—but it was largely ignored. Why did we think our outcome would be any different? The solution to Afghanistan’s quagmire cannot be solved with a military intervention. And so, twenty years after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, and a cost of over $2 trillion, the country will once again become the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.”

Military intervention did not work in Afghanistan, nor did it work in Vietnam, or Iraq, and yet, according to John Sopko, Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, “We will do this again.”

With the Taliban take-over, sadistic, cruel behavior will be accepted as normal. Little boys will grow up in a society where women are absent in public life; gone from the streets, gone from schools, gone from the workplace. These same little boys will watch and learn as their fathers routinely humiliate women, beat them, force them into burkas, and deny them any semblance of a normal life, all in the name of religion. How can we be surprised when these little boys grow up to perpetuate a skewed, pathologically brutal, and oppressive society? That is the sadness. The world is watching; more to the point, the little boys of Afghanistan are watching.

Photo Credit: Jo Carter Bowling, Afghanistan Peace Corps Volunteer